The Heartbreaking Oversight in Conversion Therapy Bans

Elijah Plummer at age 11, taken before his baptism. Courtesy of Plummer.

In 2016, at a church in Queens, New York, 16-year-old Elijah Plummer remembers feeling adult hands thrust upon him as members of the church, speaking in tongues, tried to remove his same-sex attraction “like an exorcism” in a treatment called deliverance. “I remember it in flashes. I remember the screaming,” he says.

“I rebuke the demon of lesbianism or homosexuality out of you young man!” he remembers the leaders of the service, inspired by the Presbyterian faith, yelling.

After hours of chanting and praying for him to be “freed of his homosexuality,” Plummer says that sleep deprivation and hunger would kick in.

“There were services where my voice would be broke, like, gone,” he says. “I would be drenched in sweat, emotionally shattered, and exhausted. I would be screaming for hours and hours asking God to save me. And then I have to go to school the next day.”

We reached out to the church and they did not respond to a request for comment.

Conversion therapy is a practice that aims to change the sexual orientation or gender identity of LGBTQ people. Countless studies have proven that conversion therapy does not work. A 2019 report from UCLA’s Williams Institute found that those who went through conversion therapy were twice as likely to consider and attempt suicide than those who hadn’t experienced it. And a 2018 study found that teens who experienced conversion therapy developed “lower levels of self-esteem, social support and life satisfaction, and lower levels of education and income in young adulthood.”

One would think what happened to Plummer would surely be banned today. Since 2016, there has been a swath of headlines that illustrate how 23 states—including Kentucky earlier this month—have banned conversion therapy. This has led the public to believe that it’s becoming less of a problem. But the truth is these laws only apply to licensed psychologists who practice on children. That means it is still perfectly legal nationwide for religious leaders to practice conversion therapy on anyone of any age.

The issue with this is that the majority of conversion therapy in the U.S. is administered by religious leaders. The Williams Institute estimates that while 16,000 LGBTQ youths ages 13 to 17 will receive conversion therapy from a licensed therapist before they turn 18, as many as 57,000 will receive it from a religious or spiritual adviser.

“They say it is an interference on freedom of religion and interference on freedom of speech,” says Marie-Amélie George, a Professor of Law at Wake Forest University who specializes in LGBTQ rights.

Curtis Galloway, founder of Conversion Therapy Survivor Network, says because of this nuance, the laws don’t have much impact. “Ninety-five percent of people [in the network] would not fall under the protections of the laws that are in place.”

Almost 80 survivors in Galloway’s network have reported going through conversion therapy and many of them by religious leaders. In Nebraska, one survivor reported experiencing conversion therapy at Parkview Baptist Church. In Charleston, at Christ Temple Church. And in California, at Living Waters. All three churches did not respond to requests for comment.

Galloway’s organization hosts Survivor Sundays online with 15-20 people showing and more and more people joining. “We have to add another weekly meeting,” he says.

Curtis Galloway as a teenager. Courtesy of Galloway.

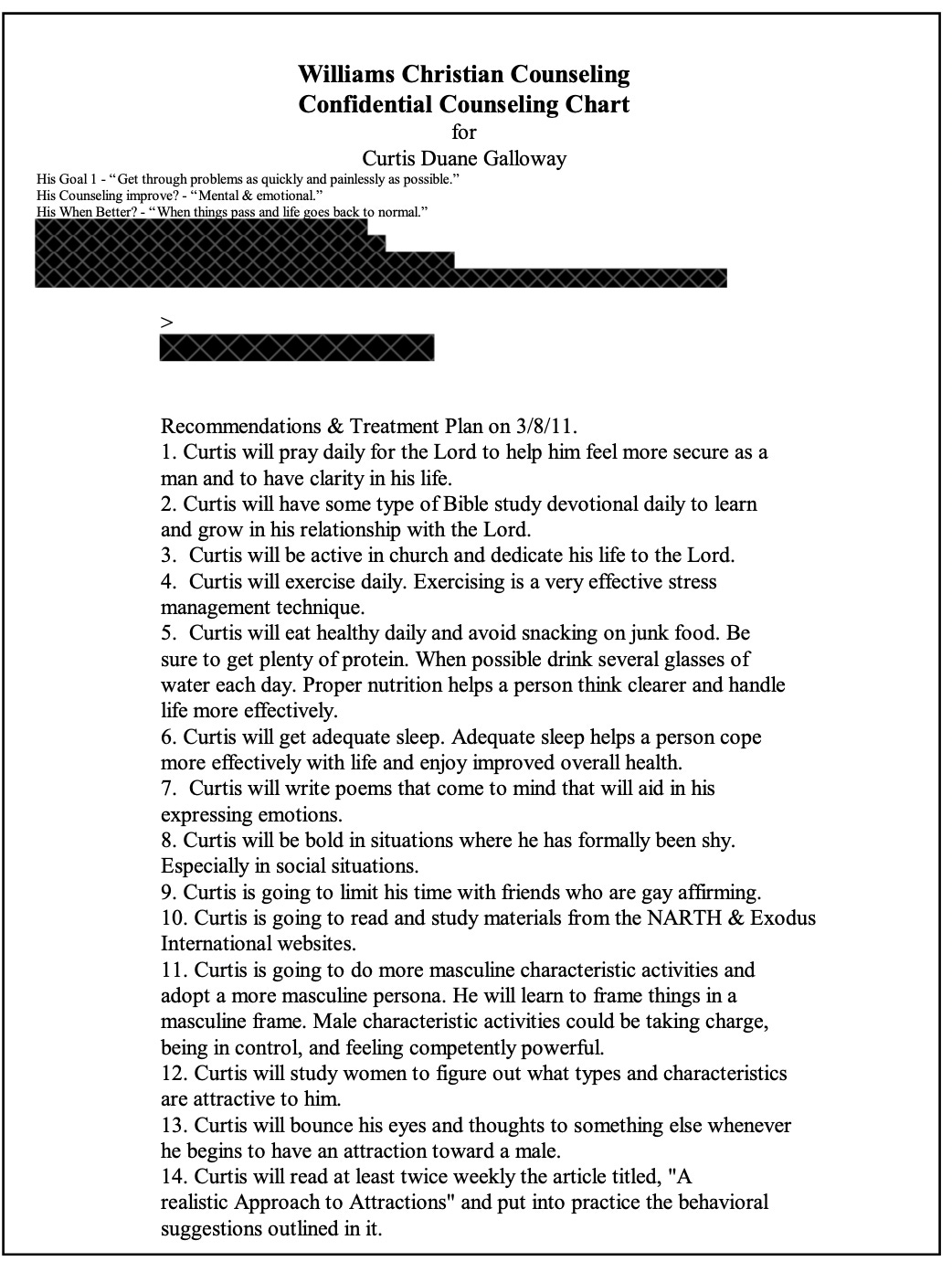

Galloway created Conversion Therapy Survivor Network in 2019 after his own experience as a teenager in Kentucky, where he was berated by a therapist for not being masculine enough, told to limit his time with gay-affirming friends, and, according to a treatment plan he shared, instructed to “study women to figure out what types and characteristics are attractive to him,” and “bounce his eyes and thoughts to something else whenever he begins to have an attraction toward a male.”

Curtis Galloway treatment plan, courtesy of Curtis Galloway. Williams Christian Counseling did not respond to a request for comment.

One of the survivors in Galloway’s network is 41-year-old Samuel Nieves who grew up as a Mormon in Utah.

“What hurt more than therapy was when my religious community would hurt me,” says Nieves, an IT healthcare consultant who lives in Seattle.

“I learned how to try to pray myself away ever since I was 13 because of the church. I was praying, trying to ask God to remove my homosexuality and how depressed I was because it was still there. That created way more pressure for me to hate myself than anything the therapist ever said.”

Samuel Nieves as a young adult, courtesy of Nieves.

He remembers the church telling him being gay was a choice and he needed to listen to country music, play football, and do more masculine things in order to correct himself. He says he was told to end his friendships with people who were accepting [of homosexuality], and that he was publicly shamed for being queer by being forced to sit out communion and other sacred practices.

Under pressure from his church, which was his main support system, Nieves internalized that something was wrong with him because he was gay, and, over the course of two years, sought conversion therapy from five different licensed therapists who claimed to heal homosexuality.

Similarly to what was discussed at church, the therapist he was seeing 20 years ago through Brigham Young University student counseling, Michael Buxton, told him to go fishing with his dad and “find a way” to enjoy a Playboy magazine as treatment.

Buxton told Uncloseted Media that he’s “very embarrassed” that he might have said that but it was a different time and people were “begging [him]” to cure them of homosexuality.

“I learned firsthand it’s only harmful and drives people further into self-hatred, and I regret that very much,” he says. “It puts both them and their partners in a very difficult life position.”

Through the 1970s and early 80s, conversion therapy was a relatively accepted practice by licensed therapists until ego-dystonic homosexuality—which was a mental disorder that described the conflict between a person’s sexual orientation and their idealized self-image—was removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1987.

With that removal, religious groups took the baton and formed groups like the National Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH). “Conversion therapy has been around for a very long time, but it didn’t become primarily that of religious people and lay counselors until they removed [ego-dystonic homosexuality] in 1987,” says Law Professor George.

In the last decade, conversion therapy of all forms has become more internationally condemned. As of December 2023, fourteen countries have banned the practice by any person including religious leaders. But George doesn’t see the U.S. joining this list anytime soon.

“Socially, the idea that people can say whatever they want is a really deeply held American principle, rightly or wrongly and it is not true everywhere else in the world,” says George. “ I think it’s worth reminding people that [the U.S.] is unique in that sense. In other parts of the world, this isn’t an issue of debate. You could ban hate.”

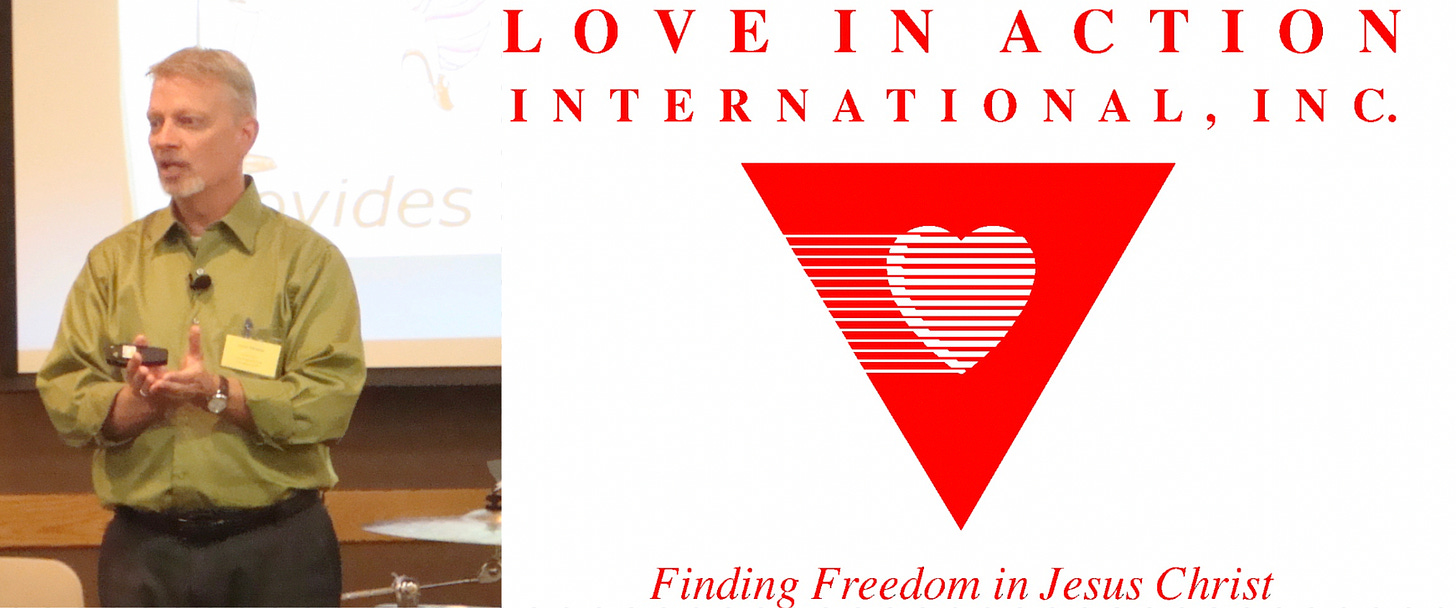

John Smid, now openly gay, counseled “thousands” of people through religious-inspired conversion therapy at conferences and live-in programs in the 22 years he worked for Love in Action, a famous religious-based conversion therapy service that shut down in 2012. He says that banning one type of conversion therapy doesn’t work. “You have Christian counselors who don’t live by those standards because they think they’re above the law,” he says. “You’ve got pastoral counselors that aren’t licensed, so they don’t care. They don’t have to abide by that. You have pastors who just want to hit people with the Bible because they believe [being gay is] an awful, terrible sin.”

John Smid at Love in Action live-in program. Courtesy of John Smid.

Elijah Plummer, now a 24-year-old recent graduate with a degree in psychology, says that he wishes there was a hotline where he could have reported what was going on at his church. “There should be a way for kids to report what’s going on,” he says.

Elijah Plummer, 24, at graduation with his Mom (left) and brother (right). Photo courtesy: Plummer.

Smid says he didn’t realize the dangers of conversion therapy when he was practicing it and that more awareness among religious leaders is an important step to reducing its prevalence. “When I saw how well-adjusted and productive LGBTQ people were when they never had to endure that shame I realized how deeply harmful it was for those who were suppressed, forced, manipulated into that kind of overbearing religious condemnation,” he says.

“The only way to affect the religious leaders in this matter is ongoing education, stories, and facts. Continue to gather stories not only of those that were wounded but the effects on humans regarding shame.”

Courtesy of Samuel Nieves.

Twenty years after going through conversion therapy, Sam Nieves still gets triggered. The song No Air by Jordan Sparks and Chris Brown came on when he was with his family earlier this year, and he was brought back to his teenage self trying to pray himself away.

As conversion therapy persists in religious circles nationwide, the LGBTQ community continues to struggle with mental health. A recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that more than 40% of LGBTQ youth seriously considered suicide in the last year.

“The hardest part has been fighting for ten years to no longer be suicidal every single day,” says Nieves, who has been married to a man for 13 years and uses the Instagram handle @cantpraymeaway. “I would say that’s the hardest part that probably every survivor would agree with. Everything that I cared about was a lie, and everyone I cared about is gone.”

“Conversion therapy survivors like myself are constantly saying that we don’t know who we are,” Nieves says. “We don’t know how to enjoy life. They broke our spirits. Now, even though I’ve been married for 13 years, I feel like I’m only finally now just starting to learn how to enjoy life and have self-confidence and stand up for myself.”

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button: