Navigating health care in an anti-fat and anti-Black world

At the time, I couldn’t name the feeling. How can a child, no older than ten-years-old, articulate the unique discomfort of a cold, sterile exam room while adults discuss her weight? Already so used to bottling up my feelings, I sat there trying to choke back tears, the tingle in the back of my throat intensifying with every word that made me fold into myself. High cholesterol. Diet. Lose weight. By the end of the appointment, my pediatrician became another person who made me ashamed of my weight. Another reason to cower and fold into myself. Another lived experience to build onto my impenetrable walls of safety. Those words, dripped in concern and laced with disdain, hurt me.

I walked out of the office with my head hung low in shame and my own weight on my shoulders, almost like the innocence of childhood was taken from me. I had to grow up with a big, fat monster hovering over me, reminding me that I’m not like others. I’m damaged and should be ashamed for the way my body looks. Negative body image has entered the chat, right at the start of my adolescence and the “Childhood Obesity Epidemic.”

On October 26, 1999, the CDC (Centers of Disease Control and Prevention) posted a press release to name and address the problem that needed to be eradicated by any means. In the press release, then CDC director, Jeffery P. Koplan, expressed grave concern about overweight and physically inactive Americans, stating “obesity is an epidemic and should be taken as seriously as any infectious disease epidemic” (CDC, 1999). Suddenly, fat bodies are classified as diseased and inherently bad, a moral failing of the people living in those bodies. Additionally, this classification created a more acute fear of “catching” fatness, and a desperation to police and get rid of fatness, and opened an even larger market for the weight loss industry.

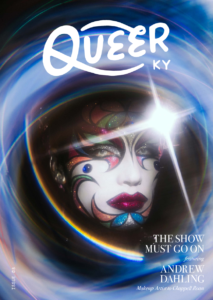

Art by Andy Mendoza

Although the extremities taken to treat obesity puts the lives of fat people at risk, Cardel and Taveras (2020) suggests a cost-benefit analysis of treatment and potential risks of those treatments. They specifically name disordered eating as a risk, and despite the fact that eating disorders “carry one of the highest mortality risks of any psychiatric disorder,” they continue to suggest that “obesity treatment programs must consider the balance between the harms of excess weight and those that may occur from weight management.” When weight is used as a measure of health, losing weight is always the “cure”. Scientific conclusions like those that prioritize weight loss over lives, aid in the dehumanization of fat people, and lead to medical professionals disregarding symptoms and misdiagnoses for fat people.

Within minutes of my first appointment with a new primary care physician, I was asked if I want to lose weight because I’m a great candidate for weight loss surgery. After reluctantly saying yes (because that’s what I should want, right?), he gave a list of documentaries to watch. One of those being Fat, Sick, and Nearly Dead, a documentary about a man drinking only fruit and vegetable juice for 60 days. A healthcare professional suggested a documentary that showed disordered eating habits. After a few more visits I stopped going, and that experience aided in my reluctance to seek treatment, which significantly informs my slight case of hypochondria.

That anxiety I experience about any health symptoms is one of the main causes of my panic attacks. Knowing that my Blackness

and fatness will cause health professionals to not take my symptoms seriously and make me feel embarrassed about my weight, I hesitated on seeking help until I start thinking about my ignored symptoms possibly leading to my death. I now feel comfortable with most of my physicians; that feeling of shame is not so haunting, and I am more equipped with the knowledge and more confident in advocating for myself. Not everyone has those tools, nor should they be expected to fight systemic health inequities.

The onus should be on health professionals, teaching more compassionate care, and educating them on the ways systemic discrimination impacts the healthcare marginalized communities receive.