Country Queers Project Shares Stories of Rural LGBTQ+ Life Through Book and Podcast

Rural queer and trans people hear all sorts of stories about how the rest of the world views them. These stories are so rarely told by the people who are living them, and often, the whole story doesn’t get to be shared. So, what does it really mean to be a Country Queer?

Country Queers is a project that was started in 2013 by Rae Garringer (40,they/them). The project began as a way for Garringer to overcome isolation from other queer folks at home in West Virginia.

Rae Garringer – photo by Lou Murrey

The project is a collection of oral histories of rural queer and trans folks. Country Queers has a lot of goals it seeks to accomplish, such as documenting the history of queer folks that may not otherwise have a voice. The project also fosters connection, and challenges stereotypes about what it means to be queer and from a rural area.

“It was born out of this frustration that I had that at that time there was almost nothing available in terms of representation of rural queer and trans people,” they said.

While there were a few academic articles that were hard to access, or pop culture films that were rooted in violence experienced by queer folks, there were little to no stories told about rural queer joy, and love. Garringer, with no experience at the time, set out to make connections with and tell the stories of country queers.

The project has evolved to incorporate different forms of media and as of 2020, Garringer, with the support of an editorial team, launched season one of the Country Queers podcast. The podcast focuses on individual rural queer folk, telling their stories in many ways with methods such as interviews and audio diaries. An audience of rural queer folks found themselves with an easier way to interact and connect with the project, and each other.

As more queer people became aware of the project, Country Queers saw a quickly growing number of engagement from the community. Garringer received messages from people all over the world “who were just so excited for this representation, and felt like it had really been missing their whole lives,” Garringer said.

“That’s always been the goal for me,” they said. “It’s for other country queers who need it like I needed it.”

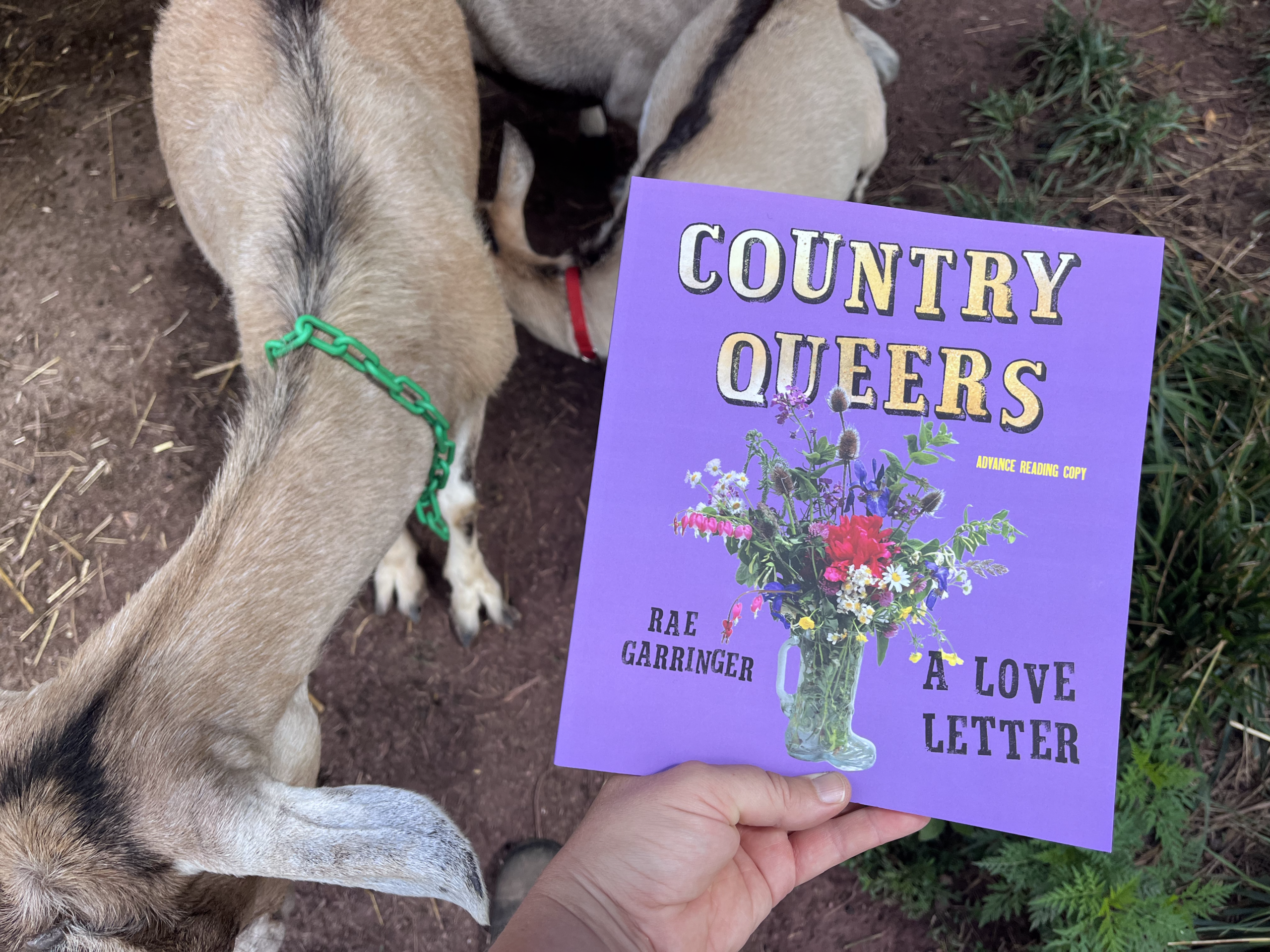

In October 2024, Garringer published a book that has felt especially rewarding for them. In the early days of the project, they shared their dreams of one day creating a book about the oral histories of rural queer and trans people. When they officially began creating the book, they were able to speak to some of these people again for the first time in several years, and hear about the ways the project has influenced them.

The book, “Country Queers: A Love Letter” contains full-color photos of queer folks and their lives, as well as documentation of interviews with them. Garringer travelled across the south and midwestern United States to collect the stories within its pages, and the book documents their experiences as an interviewer as well. “The book was the original dream when I started the project in 2013,” they said.

“In many years since then, I had actually given up on the idea of a book.” Garringer faced many challenges trying to achieve their dream of creating a book that connects rural queer communities.

“Oral history is really slow work,” they said, “I really prefer to do it in person, I actually didn’t do any remote interviews until the pandemic.” As a person traveling between rural communities in the U.S., which can be incredibly spread out, doing in person interviews was costly and time consuming.

Funding has been a hurdle for the project, as it doesn’t fit into the traditional guidelines to qualify for many types of grants or programs. Garringer had been trusted with personal stories from over 90 people, and wanted to share them with care. Finding the resources to do so was not an easy feat.

The podcast helped to achieve the creation of the book by expanding the project’s interactability and outreach, but it was not without challenges either. The main issues were things like unstable internet connections in rural Appalachia, and bad cell service.

Despite all of these obstacles, Garringer continued to work to tell the stories they had been collecting for nearly a decade. In the last few years, that work has proven to have been successful at informing others about the experiences of rural queer people.

“My editor from Haymarket reached out in the summer of 2022 and asked if I’d want to talk about publishing possibilities.”

“I’m really grateful to all the people who shared their stories with me,” Garringer said, “it’s a really generous gift, I think, when people trust you enough to share these kinds of really personal stories.” For them, this project was a collaborative effort with all of the people they spoke to. “It wouldn’t exist without them. I think they should get as much of the credit as I do.”

Country Queers has been able to put a spotlight on the experiences of rural queer individuals. With the level of fear and uncertainty in this country under the Trump administration, these stories may have a lot to offer on a national scale. “I think rural queer and trans people…have a lot to teach people nationally about surviving in these kinds of political realities because we’ve already been doing it.”

Projects like Country Queers that connect various queer communities can be significant in helping in many ways with things like isolation, social outcasting, and self image struggles. Rural queer folks know the importance of community, as well as the challenges to find it. Country Queers works to discuss all of these realities, creating connections one day at a time.