Voice Cracks, Backing Tracks, and Comebacks: How to Steer Your Changing Voice on Testosterone

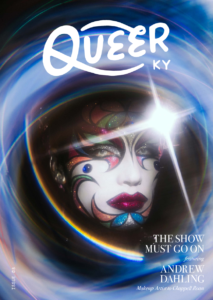

This story is part of Queer Kentucky’s digital issue surrounding the trans youth experience in the Bluegrass state, featuring personal essays to educational information. Read the full issue here.

In the moments of catharsis post-performance, I receive the most touching reminders of why I keep showing up authentically on stage despite fear. Chugging stale ice water at the bar, I can be pleasantly interrupted by a polite and energetic “would you mind if I asked you a personal question?” Usually, nervous, they follow it up with “so how long have you been on T?” I know how much it would have meant to me pre-transition to have someone like me to talk to. My expertise lies in testosterone gender-affirming hormone replacement therapy’s effects on singing, but the techniques can help singers of all backgrounds. Beyond technique, the most challenging part of my vocal transition has been the emotional one, and this seems to be a shared theme amongst questioning and trans vocalists.

I wrote my first song in kindergarten. By the age of fourteen, I learned how to play acoustic guitar. I started performing my songs at an open mic in Lexington called LexJam. From there, things accelerated quickly, and soon I was on Woodsongs Old-Time Radio Hour, gaining national radio play. Local news station airtime, local small festivals, and eventually paid gigs. I recorded a single and released it on all platforms when I was 17. Soon, it was getting played on BBC Music Introducing in England, and I was headlining Red Barn Radio just like one of my personal heroes, Tyler Childers, and opening for the great Louisville-based songwriter Mark Charles. I performed in New York City and Ireland. Yet something didn’t feel right. You, dear reader, might know the feeling.

By the time I was 18, I could no longer ignore that something was wrong. In order to write and sing truly great music, you need to be able to sit with your inner thoughts for extended periods of time. You need to allow your body and voice to take up physical, emotional, and spiritual space. I didn’t feel like I deserved that space anymore. According to Cleveland Clinic, singing activates your parasympathetic nervous system and stimulates the vagus nerve, which runs down from your ears (listening), to your throat (vibrating), to your lungs, diaphragm, and gut (expanding and contracting). I know now that the act of singing was forcing my body to rest and release the tension and trauma I was holding.

I delayed my transition for a long time due to fears about “ruining” my singing voice or career. How would I adjust to a completely new tone? When I took my first T shot, I began researching transmasc and trans male singer-songwriters like Eli Conley. I learned that cis boys’ vocal cords get thicker and longer during puberty. When undergoing testosterone gender-affirming HRT, the vocal cords just become thicker, not longer. Knowing this, you can deepen your range while at the same time maintaining your higher range, albeit with a different timbre. For me, it became an opportunity, not a negative, and I started to think of it like a fun challenge.

- Finding Your Current Range: Locate a piano, or a free piano app. I recommend singing ascending and descending major scales, alternating between vowel and consonant sounds. Try sliding your voice like a slide-whistle ascending and descending like a siren. Warmup your breathing muscles as well; take long deep breaths and “hiss” until your lungs are emptied.

Before singing, make sure you have the proper posture: spine straight, and shoulders down and relaxed. If you are sitting, make sure your feet are firmly pressed to the floor. If you are standing, make sure your feet are roughly shoulder-length apart. Press “Middle C.” Match pitch in any way you’d like: humming, vowel sounds, vocalizations, etc. Ascend one piano key at a time and match pitch until you reach a note that feels uncomfortable to sing. The last comfortable note will roughly be the top of your range. If you are using a piano app, it will likely tell you the exact note and octave, such as C4. Write this down. Repeat the same steps as above, but descend. Write that down. Now you have a rough estimate of your vocal range. According to Yale University, the vocal ranges are as follows:

soprano: C4 to A5

mezzo-soprano: A3-F5

alto: F3-D5

tenor: B2-G4

baritone: G2-E4

bass: E2-C4

- Find a Model Voice: After you’ve identified your range and vocal type, search for vocalists with your current vocal range, or the vocal range that is adjacent to your current one. For me, that was Tyler Childers. Having a model can help you “place” your changing voice. It’s like going from playing a tenor trombone to a bass trombone – you will have to create muscle memory for new “positions.” Instead of using a slide to change notes like a trombone, you will change the position of your soft palate, larynx (voice box), and facial muscles. Sing along to their songs. Have fun with it and don’t worry about how you sound, just try to match pitch. Try singing their songs while scrunching your nose, raising your eyebrows, or moving your tongue to try and “feel” different methods of vocal resonation. You may find something that feels right for you!

- Frequent Practice: Consistency is key. Just like with exercise, it takes frequent practice in order to build up strength. Try these exercises in a consistent routine to build strength, control, and power with your voice. Make sure to rest your voice as well – overusing your vocal cords can lead to injury.

-

-

- EE AH: Alternate singing the vowels “EE” and “AH” in succession. This opens up the pharyngeal walls of the pharynx

- Siren: Play the note at the bottom of your vocal range on a piano. Match pitch and slide (like a slide whistle) up to the highest note in your range and back down again. Make sure to take a big breath beforehand. Your shoulders should not be rising significantly each time you breathe. Imagine your breath expanding from your lungs downward into your pelvis. This helps you learn to control your larynx (voice box) and breath.

-

- HO HO HO: Locate your diaphragm. A great way to locate your diaphragm is by touching your bottom ribs, then walking your fingers across them to the middle of your body. Do a fake cough. The firm muscle that presses into your fingers is the diaphragm, which helps your lungs push air out of your body. Take a deep breath while pressing on this muscle, and do a few “HO HO HO’s” like Santa Claus. Some studies show that touching the muscles you are activating increases the mind-muscle connection, muscle activity, and muscle growth (source: Oshita).

- Do Mi So Mi Do: This is another classic warmup for a reason. You sing the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 1st notes in a major scale, vocalizing “Do Mi So Mi Do.” Additionally, “Do Mi So Do So Mi Do” is a great exercise.

- Yawn: Intentionally and repeatedly raising your soft palate by “yawning” is an excellent way to strengthen it. Control of the soft palate is vital for vocal tone and resonance.

- Sing Your Old Music: It was healing to me to try and sing my old songs using my changing voice. I would recommend the same. Try singing it in a different key, or slightly altering melodies to fit your current range.

- Write New Music to Match Your Voice: The biggest breakthrough for me was when I stopped moping about not being able to sing my old songs in the exact same way. Try this exercise: find a chord progression your model voice used. Use the same chords in any order and sing gibberish in any melody you like. This may help you brainstorm new ways to create melodies in your current vocal range.

Allowing yourself to listen and feel your own vocal changes is essential. I’ve been on T for 2.5 years and can sing deeper with higher altitudes. My voice matches my internal sense of self. I go through vocal “growth spurts” periodically. I’ll have finally “figured out” my voice, range, and tone for a few months, and then suddenly my range will decrease again due to my voice changing. Through performing in public during my transition, I have been able to connect with like-minded queer people and musicians I never would have met otherwise. Feel free to watch my video performing Tyler Childer’s “You’re All Mine” on TikTok. My advice is to give yourself some grace. Voice cracks are a sign of your strength to move forward. It will take time, and it’s different for each individual. If you loved performing before your transition, keep going. Your love of singing and songwriting may be a powerful therapy throughout your transition.