Acid, Ache, and the Grief Behind the Glamour: A reflection on substance abuse, recovery, and the ghosts, glitter, and grime in between.

This story is part of Queer Kentucky’s digital issue surrounding the trans youth experience in the Bluegrass state, featuring personal essays to educational information. Read the full issue here.

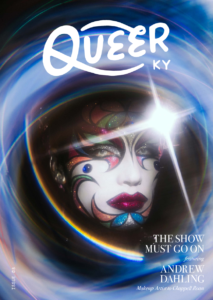

Photos and story by D.L.

It was 2023. The world had been ending for three years, but my world was ceasing to exist. My family home burned to bits two years prior, my uncle’s breath was flattened by fentanyl months later, and my grandfather had just been crushed by cancer. Death followed me like a dog. In my new adulthood, I fled Louisville, thinking it might not find me. I was 19, suicidal, and believed if I wanted to survive, I needed to be numbed.

Then I tripped.

On acid, I was anything but numb. I was honest with myself. Despite the fact that I was tripping to forget the grief that defined my life, I spent most of my trips remembering the people I’d lost. I could remember their laughs without shutting down. I could remind myself that I’ll never see them again and somehow survive. I felt halfway-human again.

When I tripped, I acknowledged death and grief as part of the incomprehensible human experience and accepted it the same way I accepted any mind-fuck on psychedelics. When I was sober, only two things mattered:

- People I love are dead.

- There’s something I can put in my body that makes me feel like I’ll survive that.

I spent seven weekends straight searing my brain too stupid to hurt. I avoided sobriety in an effort to evade sadness and how scared I was. In public, I was uncomfortable. At home, I was anxious, like every second spent sober was grief catching up.

On acid, I soaked in a technicolor, spiraled version of my world. I felt everything completely. Every touch was 200 volts of pure, white-hot pleasure. Every emotion was an energetic pulse of ecstasy. I saw heart-shattering beauty in everything and everyone. I had never felt so connected to music, strangers, and myself.

At first, it felt glamorous. I was doing drugs in a big city, mentally unravelling and surrounded by sweat-soaked, sparkling strangers and brain-buzzing bass, held together by nothing but torn fishnets, pasties, and a pink feather boa. I had more fun than fear and got high on the glory of parading my body while destroying it.

I’d never shown so much skin. I grew up bulimic, and before I started raving, the most positive relationship I’d had with my body was centered more on acceptance than any sort of love or confidence. Being chronically ill, I also had a complex relationship with my body and the physical pain that comes with living in it.

It shocked me how supportive the community is. I understand the push toward body neutrality, but to be seen so clearly and to have my style, creativity, and appearance complimented constantly was cathartic. It was impossible not to feel good about myself when beautiful women were saying I was the sexiest person they’d ever seen.

Besides that, I enjoyed the freedom of getting to be topless in rave and festival spaces regardless of my gender. I liked that even if they wouldn’t remember them (typical), nobody looked at me weirdly for saying that my partner and I use they/them pronouns, because to do so wouldn’t uphold PLUR(R) – Peace, Love, Unity, Respect, and (the often omitted) Responsibility.

With this newfound confidence and freedom, my outfits became increasingly revealing. I knew outwardly, to many, I looked like a party girl who was doing too much for attention. But I adored the euphoria that came from being myself, being comfortable in my skin, and feeling seen.

At my first raves and festivals, I pretended there were no preconceived notions about my body or gender. I felt like a ninety-percent-naked, genderless fairy flitting around the woods, surrounded by people who only noticed the music, not my body.

This was delusional. I was groped and misgendered often, sometimes by people I considered friends. People who sexually assaulted me were seeing and enjoying my body and outfits from a place of perversion, not expression. I’m not ashamed of sexuality and value it both in my presentation and as nature, but being groped while incapacitated on drugs is obviously neither a sensual nor consensual experience, and showed me how I was truly perceived: a nearly-naked woman too high to defend myself.

I can’t say I’ve never harmed people on drugs. I let relationships fizzle out because I was putting more energy into escapism than I was into any of the living people I love. I was selfish. My brain was curdled. Even sober, I was an alien disconnected from everyone – and ironically, it was because of the drugs I took to feel connected to people.

On acid, I was no better. I was incoherent and often either too affectionate or standoffish. I prayed that people considered my uncomfortable behavior whimsical (at best) or wooky (at worst), but looking back, I was just sloppy. I felt like my substance use couldn’t be as bad as it felt because friends were still seeking me out at events, still saying they loved me, still saying I was fun to party with. But I woke up steeped in shame after every night out.

Maybe I was fun. Truthfully, I wouldn’t remember. And that was the much larger issue. My feelings on the subject are best summarized by the way my friend explained her sobriety from cocaine: “I’m tired of having no memory of the best nights of my life.” And I’m tired of the memories I do have being shrouded by shame.

For me, the most euphoric part about any rave is being so overtaken by the love for the music and people that I forget to care about how I look dancing and just move and feel. I deserve to be present in that, and I want to remember it.

In the darkest depths of my addiction, I needed to understand that the false dichotomy of drugs being “good” or “bad” wasn’t going to save me. More than I needed to quit any substance, I needed to sit with the reality that I was using drugs to distort. Being constantly high was destroying me, but so was stifling the hurt beneath it.

Two years later, I’m able to find beauty in the world and can feel what is distinctly ugly, painful, and difficult without the buffer of substances – I love the complex, grief-filled world and body I live in enough to not chemically sever myself from them every chance I get.