Meet Joy Cedar: The Two-Spirit Artist, Activist Reclaiming Land and Nourishing Queer Hearts

There’s beauty and power in fluidity, and artist and activist Joy Cedar knows this better than most. The multi-disciplined painter and poet from Letcher County is known for weaving wordplay into their visual art as well as their activism in Eastern Kentucky. Now based in Lexington, the 34-year-old, two-spirit Cherokee descendant is infusing the local queer community with Indigenous pride and infectious optimism.

“I’ve always been writing poetry,” Cedar said. “My mom was a school teacher. She taught kindergarten and first grade for 27 years, so she always really encouraged me to write and to process the world through a written lens. And as I got older, I started sharing them with folks and every now and then, one of my poems would really resonate with somebody, or I would be able to use it in activism work. [Writing is] a way to stretch certain muscles, and I like the ability that poetry gives you to be intimate with the reader and to let them in in a way that everyday conversations really don’t give you.”

Three of Cedar’s poems were just published by The University Press of Kentucky in the new book, “To Belong Here: A New Generation of Queer, Trans, and Two-Spirit Appalachian Writers”. Last month, they did a reading at their favorite bookstore, Read Spotted Newt, in their hometown of Hazard. “That’s an excellent bookstore to go by and pick [the book] up,” they said.

One of the poems in the book focuses on their two-spirit identity and how the term means so much more than many non-Indigenous people realize.

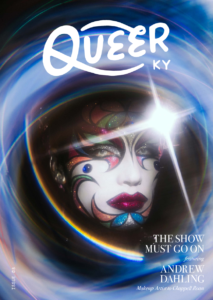

“The Land” created and photographed by Joy Cedar

“I think two-spirit is the most effective label because it encompasses that my queerness does come through a cultural lens and is expressed in a cultural way,” they said. “If I were talking to just settlers who don’t have a frame of what two-spirit might mean or what it might mean to my community, I would say bisexual, non-binary. Two-spirit encompasses it more because my people have words for the specific lane that I’m in.”

“Previous to two-spirit being used,” added Cedar, “the words that were used for us were often chosen by people who weren’t us. And so those words were often offensive, and the umbrella terms we got were really harsh and inappropriate. So there’s something really beautiful, too, about this being a community-chosen terminology.”

In addition to reclaiming language, Cedar is helping reclaim Indigenous land in Kentucky as the executive director of the Appalachian Rekindling Project. They’re also a member of local organizations, such as Kentucky Tenants. Cedar deeply cares about their people and community. “I think we have to, right?” they said. “Like, that’s the whole point of existing on the earth at the same time. It’s making sure we all get through it.”

“I’m a dogged optimist,” they added. “But because I am a dogged optimist, I get to do really cool things. We acquired land that was going to be a prison. So the dogged optimism it does win out. If you believe that there can be something better, sometimes there can.”

Of course that doesn’t mean that Cedar is oblivious to how bleak the queer community feels right now, as rights are rolled back. But, back to their dogged optimism, they believe we can’t lose everything.

“I believe that creative pursuits are cultural wealth, and it’s a wealth that can’t be taken from us,” they said. “As everyone’s talking about ‘in this moment, in this time,’ and all of the things that we’re losing, I hope we remember that we have wealth that can’t be extracted from our community—and creativity is part of that.”

Cedar is determined to share that wealth by leading art workshops at The Pond, a queer multi-use art space in Whitesburg. Their favorite session to teach is DIY paint—as in, making your own pigment from scratch.

“I’ll forage for pigments and then process them and make them into my own paint,” they said. “Sometimes they’re watercolor, sometimes they’re acrylic. It’s very fun. I love that process of being involved in materials the whole way through.”

“My personal favorite are violets,” they added. “I’m a big fan of creek rock—like getting into the creek and choosing whichever rocks you think are pretty. All rocks have pigment, but the ones that act like chalk when you rub them on another rock, that’s really what you want. I’m also really fond of using food waste as a pigment. An avocado peel gives the nicest, soft maroon. And I just like for people to know that if you’re going to throw away your avocado— wait! Dandelion makes a great color, too. The leaves of a dandelion do as well. And pokeberry! Incredible pigment. Highly recommend. If you’re making poke salad, obviously you’re going to throw away the berries because they’re poisonous, but before you do that, they can make some great pigment either for paint or a direct ink. It’s really gorgeous.”

“Quilt” created and photographed by Joy Cedar

Two of Cedar’s paintings (with natural, homemade paints) are currently on tour with the Kentucky Arts Council in the “Native Reflections” exhibit. The final tour stop will be this month at John James Audubon State Park, but Cedar’s art can be viewed virtually on the arts council’s website.

“One of [the paintings] is a commentary on Palestine,” said Cedar. “And it says in Cherokee, ‘Treat each other’s existence as being sacred.’ And I have a portrait piece that’s a rough oil portrait. Folks can go see those for free with other artists who are Indigenous and in Kentucky.”

It’s still unknown how much this year’s House Bill 4 and HB 9–two anti-DEI initiatives–will impact arts and culture funding in Kentucky and what that means for the future of Indigenous art grants in the state, but Cedar is quick to launch that dogged optimism.

“They can defund an art program, but I’m still going to make paint in my backyard,” they said. “ And I’m going to teach people how to do it. So, there’s no amount of defunding that’s going to change the heart of an artist, you know, or the fact that art will feed the queer community.”

And right now, the community needs nourishment. The hits just keep coming, depleting spirit, from safety concerns for queer parents to non-stop, anti-trans nonsense in the military. It’s hard to feel full while running on fumes. But Joy Cedar is proof that art is a crucial connective tissue in the queer community. And the more queer creatives can bridge multiple nooks and crannies in the queer community—dire issues such as food insecurity, racial equity, and gender justice—the strong the queer community becomes. Artists like Cedar aren’t just feeding the community, they’re building muscle.