The Agony of the Leaves: Reflections on Tea

Photo Courtesy of Margaret Hamilton and Emily Gibson.

As early as I can remember, I’ve been a student and lover of tea, Camellia sinensis. Green tea was my preferred beverage growing up, and if given a choice between tea, juice, and soda, I would choose green tea–preferably with honey and fresh lemon. Tea replaced my water consumption because, in my mind, it was just leaf-flavored water. My family and friends would often joke about how much I loved tea, and tea became the go-to holiday gift for me. One day, I went to see my pediatrician for fatigue, where it was discovered that my iron levels were dangerously low.

Photo Courtesy of Margaret Hamilton and Emily Gibson.

My consumption of tea had depleted my iron levels, which triggered an episode of iron deficiency anemia. He prescribed ferrous sulfate (iron) and placed me on a mandatory “tea break” for three months, at minimum. I had to stop drinking tea, but tea was still on my mind. How was tea able to impact my body’s ability to absorb iron? How could tea work inside my body to prevent the overconsumption of its nectar? This showed me the power of plants and that plants have their own way of asserting boundaries. I was consuming tea daily, but I wasn’t in right relationship with it. It was time to learn from the wisdom of this plant.

My study of the tea plant led me to enroll in herbalism courses, learn about urban foraging, study medicinal remedies used by enslaved populations, and curate herbal solutions for spiritual ailments. The path that tea forged for me eventually led me back to my heritage of rootwork and hoodoo. In this piece, I’ll share some notes from a Tea 101 class I taught in 2019, as well as recommendations from Kentucky tea shops.

The Agony of the Leaves

Although I postponed my dreams of becoming an International Tea Master, I still have great respect for the plant, the ancestral tea stewards, and present-day workers of the Xinan (西南), Jiangnan (江南), Jiangbei (江北), and Hunan (湖南) regions of China; the Assam, Nilgiri, and Darjeeling regions of India; and the lineage of stewards originating from Japan, Sri Lanka, and Taiwan.

I can’t help but see the similarities between the struggle for Black liberation, the desperate conditions of Palestine, Congo, Sudan, and Haiti as a result of genocide at various paces, and the urgent message to decolonize tea. As Charlene Wang de Chen makes clear, the colonial tea trading business–established by the Dutch and British in the 1600’s–“was an integral part of the transatlantic trades” for gold, silver, sugar, cotton, coffee, and black bodies like mine. When British colonizers didn’t have enough silver to purchase tea from China, they paid with opium, grown by Indian farmers, to make up the difference in cost.

When opium, which was illegal in China, was confiscated by the Chinese government, the British used this to justify attacking China, all while stealing their tea plants and agricultural wisdom to build tea plantations in India. Still today, some of the biggest tea brands operate tea estates where workers endure intensive labor, destitute working and living conditions, extreme underpayment, and exposure to sexual harassment and other forms of discrimination.

It is difficult to ignore that the same conditions that made it possible for my black mama to buy green tea at a supermarket in Kentucky are the same conditions that justified the captivity of our ancestors–that these are also people subjugated to unimaginable life conditions on a plantation for little to no pay…in the present tense. Colonizing nations depend on tea but ignore the people, cultures, and conditions that make tea possible.

Photo Courtesy of Margaret Hamilton and Emily Gibson.

Sounds familiar, right? As someone who knows what it means to be extracted from, how could I make every mug of tea become a prayer unfurling toward the hands that picked it? How could every sip become a reminder that we are intricately linked in a global tapestry of struggle? In the tea world, the transformation that happens when boiling water strikes a leaf, causing it to unravel, is known as the agony of the leaves.

The transformation that tea undergoes in the process releases the true essence of the plant and frees the leaves from the contortions of humanity. It is this unrelenting combination of heat and moisture that forces the leaves to open up and reclaim their wholeness, even in the afterlife. It is a liberatory method that we could all study and learn from.

Passing the Tea Baton

Photo Courtesy of Margaret Hamilton and Emily Gibson.

I taught my Tea 101 class at the now-closed Wild Dog Rose tea boutique. This boutique was an earthen womb that held me during a crucial part of my gender journey. I spent a lot of time there perusing the symmetrical tin can labels for the perfect tea blend, reading tarot cards with my beloved friends and tea shop owners Margaret and Emily, and talking to customers about herbal remedies to soothe physical and emotional ailments. Maybe it was the healing effects of the crystals sold there or Emily’s excellent taste in music, or the hearty fragrance of honeyed Assam CTC BOP (Method: Crush-Tear-Curl; Grade: Broken Orange Pekoe), or the constant whiffs of palo santo smoke that made me never want to leave. I was there so often that everyone assumed I was an employee. I didn’t work there, but I worked on myself there.

Though Wild Dog Rose closed its doors in the spring of 2019, Louisville’s tea legacy lives on. I have frequented Louisville Tea Company in Lyndon, Elmwood Inn Fine Teas (a regional distributor) in Danville, Churchill’s Fine Teas in Cincinnati, and Sis Got Tea, which I visited for the first time last summer. Sis Got Tea is a black-, woman-, and queer-owned tea shop that opened in April 2023 and is located in the Germantown neighborhood in Louisville.

Below, I will pair my Tea 101 notes with teas from the above shops. Read through each tea description and select one that piques your interest. Throughout the tea-making process, let the tea leaves speak to you. Experiment with applying its message in your life and witness the power of plant medicine.

Photo Courtesy of Margaret Hamilton and Emily Gibson.

Tea Families and Recommendations

Note: Tea contains caffeine.

This was an introductory tea class that discussed each family of tea: green, yellow, white, oolong, and black–all from the same plant. The class took place before the pandemic and focused on tasting and comparing notes. The notes cover brewing temperatures and times, flavor profile, liquor color, the cultivation process, and other random thoughts based on how I like my tea. I included the cultivation process to acknowledge the sacrifices in a single cup of tea.

The notes do not cover indigenous Chinese or Japanese tea ceremonies or subcategories of tea like fermented teas (sorry, pu-erh lovers), blooming teas, herbal teas, tea/kettle pairings, or pouring methods. The tea families are arranged from lowest to highest steeping temperature ranges, and all main tea recommendations are non-flavored so that beginners can become familiar with the natural profiles of each tea family and experiment from there.

Green

Photo Source: Sis Got Tea website.

- Brewed at 160-175 F for 2-3 minutes.

- If it’s Chinese green tea, it tastes like verdant, fresh earth. If it’s Japanese green tea, it tastes savory with hints of ocean and umami.

- This is the only tea family whose production does not alter the chemical properties of the leaf, therefore preserving its natural green color.

- Workers are outside all day plucking the leaves. Then, they tediously arrange the leaves to air dry. Later, they collect and heat the leaves with dry air and steaming processes.

- After drying, workers crush, twist, fold, or roll them into “pearls,” most often by hand.

- Green tea is sensitive and easy to burn. It teaches patience, observance, and gentleness. Although green tea is often the base for fruity teas, it is naturally fragrant, which teaches us that sometimes less is more.

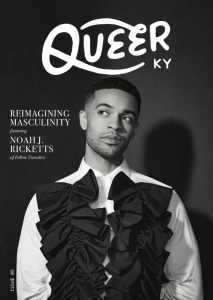

Green Tea Recommendation: Classic Sencha (pictured above) at Sis Got Tea

Yellow

Photo Source: Elmwood Inn Fine Teas website.

- Brewed at 175-185 F for 3-5 minutes.

- The hue of yellow tea ranges from pale to golden yellow.

- Tastes like a hint of roasted nuts and silky sunshine.

- Yellow tea is a delicacy in China, as there is limited production of authentic yellow tea, making it the most rare and expensive family of teas.

- The process for yellow tea is very similar to the green tea process, with one difference: after workers spend all day picking, heating, steaming, and rolling the leaves, they stack them into a pile and cover them for soft oxidization, which results in a yellow hue.

- The cultivation process makes yellow tea expensive, not the taste.

- The profile is comparable to that of light green tea but less astringent.

- If subtlety is your thing and you’re a tea enthusiast, I recommend splurging on some authentic yellow tea.

- Yellow tea teaches that it’s okay to be expensive, exclusive, and rare.

Yellow Tea Recommendation: Huo Shan Huang (pictured above) at Elmwood Inn Fine Teas in Danville

White

Photo Source: Sis Got Tea website.

- Brewed at 180-185 F for 4-5 minutes.

- The hue of white tea is pale yellow.

- Tastes like butterflies gliding in the wind and drops of honey on a flower petal.

- Tastes like bitter tears when over-steeped.

- Processing leaves for white tea does not involve heating or rolling like darker teas. After a worker plucks the leaves, shoots, and buds, the leaves are left to wither for a few days in a controlled environment.

- Once perfectly withered, workers collect the leaves in large baskets and dry them at low temperatures until they are completely dry.

- White tea contains parts different from the tea plant, including leaves, shoots, and buds. The most expensive white teas consist of shoots only.

- White tea is produced in China and the southern region of Sri Lanka.

- Oversteeped white tea is still pale but tastes very harsh. It teaches that looks can be deceiving and invites us to tap into the power of our other senses.

White Tea Recommendation: Pai Mu Tan (pictured above) at Sis Got Tea

Oolong/Wulong

Photo Source: Louisville Tea Company website.

- My favorite tea of all tea families. I’ve never met a bad-tasting oolong.

- Brewed at 195-205 for 3-5 minutes.

- Oolong produces a beautiful golden amber to dark orange hue.

- Oolongs are buttery, lush jungles, honeyed umami, and great with fruity profiles (like Sis Got Tea’s Mango Oolong).

- This process begins with someone picking the leaves, which are then left out in the sun to wither and dry in the sun. Workers then rotate, heat, roll, and dry the leaves again.

- This method is the most complex of the tea families, combining the processes of both the green and black tea families.

- Oolong has a low tannin content, making it a great tea for beginners. Even if you accidentally add too much or over-steep your tea, it will still result in a decent cup. Oolong is forgiving. It teaches us forgiveness and flexibility.

Oolong Tea Recommendation: Tin Kuan Yin at Sis Got Tea

Bonus: My absolute favs… Milk Oolong at Louisville Tea Company and Osmanthus Oolong at Elmwood Inn Fine Teas

Black Tea

Photo Source: Sis Got Tea website

- Brewed at 195-212 F for 3-5 minutes

- Black tea can vary from dark yellow to dark amber.

- What classifies it as black tea is that’s fully oxidized, giving it a dark bourbon hue.

- It tastes of sweet tobacco, of drumming and dancing in the bare earth. It is dark and surprisingly bright, often with citrus notes.

- After a worker picks the leaves, they dry the leaves in high heat, which stops the oxidization process. Then, workers roll the leaves and leave them to dry in the sun.

- In India, black tea is a cultural staple. It is blended with spices, milk, and sugar. This is chai, which means “tea” in Hindi.

- After the tea plantations in India failed, the British Crown sent a Scottish colonizing botanist named Robert Fortune to China to steal seeds, plant clippings and spy on indigenous cultivation techniques.

- Black tea teaches liberation and asks how we are living in alignment with the frequency of liberation in thought, speech, and action. In the Southern US region, black tea loves her some sugar! She teaches lessons of holding on to sweetness, even in bitter times.

Black Tea Recommendation: Kenya Black by Sis Got Tea (Bonus tip: to make it a chai, head to your local grocery to gather fresh ingredients, or get you some Diaspora Co. Chai Masala Spice Blend.)

Everything about tea is a ritual. Each family emerges from various rituals of attention and care. The hands that pluck, dry, and package the leaves expanding in your mug are experts in these rituals. Each teaspoon of loose leaf invites you to slow down and reflect on its messages. As the water slowly heats, internal peace is cultivated. So often, we are bombarded by rainbow capitalism and mainstream depictions of queerness that associate us with hard living, nightlife, and oppressive legislation. Tea is for the tender queers. Tea is for those about that soft, gentle life. Tea is for the ones who know dreaming is the only way forward. Dreams of land returned to its indigenous stewards. Dreams of a free Sudan, Congo, and Palestine. Dreams of healing and repair in Haiti. Dreams of reparative tea plantations, where the land is owned by those who work it. The agony of the leaves reminds us freedom is imperative. Not even scorching conditions can keep us from coming home to ourselves and each other.

Source for the more technical aspects of my tea notes:

Lombardi, G., Petroni, F., & Ruggieri, G. (2014). Tea Sommelier (Revised edition.). White Star Publishers.

Austen Smith is a spirit-forward visionary artist, writer, social researcher, and founder of a black-centered organization focusing on the intersection of spatial reparations, arts/culture, and spiritual transformation. Austen uses ancestral reverence and black philosophies of space/time to restore the imaginations of systemically disempowered peoples. To learn more about their work, visit www.ourlunarintelligence.org.

What a moment for Queer Kentucky!

What a moment for Queer Kentucky!

@19thnews A federal move to withhold 16 fam

@19thnews A federal move to withhold 16 fam