Louisville author’s book adapted into HBO docuseries “Murder in Glitter Ball City.”

Author David Dominé talked to Queer Kentucky ahead of the docuseries’ premiere of Murder in Glitter Ball City.

When author David Dominé was house-hunting in Old Louisville years ago, he passed on 1435 S. Fourth Street, finding the Victorian mansion too dilapidated.

Two years later, he turned on the news to learn that the same house, just down the street from his own, was the site of a grisly murder. Old Louisville residents Joey Banis and Jeffrey Mundt were accused of killing Jamie Carroll during a drug-fueled sexual encounter.

Carroll’s body was sealed in a storage container and buried beneath the home’s wine cellar, where it remained for six months before being discovered. After a trial filled with contradictory accounts, Banis was found guilty.

The case became more than a murder trial. It exposed tensions around sexuality, class, reputation, and how queer lives are scrutinized in the courtroom.

Dominé spent the next decade attending trials and documenting the aftermath in ‘A Dark Room in Glitter Ball City’, a blend of true crime, memoir, and neighborhood ethnography in which Old Louisville itself becomes a central character.

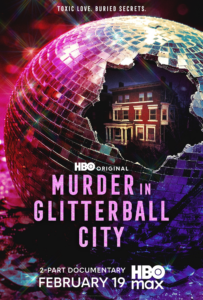

The book is now a two-part HBO docuseries, ‘Murder in Glitter Ball City’, which premiered February 19 at 8 p.m. Directed by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato of World of Wonder, known for Paris Is Burning and RuPaul’s Drag Race, the adaptation revisits the case through a distinctly queer cultural lens.

Ahead of the premiere, we spoke with Dominé, also an Old Louisville tour guide, about voyeurism in the courtroom, victim erasure, and representing queer life without sensationalism.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

What can viewers expect from the two-part series?

The book is a celebration of Louisville and Old Louisville, and the people at HBO got that right away. The documentary is directed by Randy Barbato and Fenton Bailey of World of Wonder, and when audiences see a movie from them, even when the subject matter is dark, they balance gravity with wit and nuance, creating films that are emotionally layered and unafraid of complexity. They will get this in Murder in Glitterball City.

I want to talk about the trial coverage. What was going through your head as you watched that unfold?

Right away, it’s like, well, it’s a gay couple, of course, it’s gonna be terrible, and it was. There was just blatant homophobia and kink shaming. And so throughout the story, it’s interspersed with other crimes happening in the state, the city, and the country to point out that there were other crimes. And if not as bad or worse, but no one really analyzed them the same way because they were crimes involving heterosexual people. So I tried to put things in perspective by pointing out all the other things that were going on at the same time.

I was struck by how little humanity the victim was afforded in the courtroom. The emphasis was on sex, drugs, and salacious detail, not on who he was as a person. Did you see that as emblematic of how the criminal justice system treated gay men at the time?

None of the stuff that I saw in the courtroom did anything to try to humanize Jamie Carroll. They brought up facts, and they were all indisputable things. He had been a dealer; he was selling drugs the night that they were with him. Yes, he had a sexual history with them. Well, yes.

So whenever I had the chance, I met people who knew Jamie and his friends. I really tried to find those stories that painted him with a more sympathetic brush, pointing out what a talented hairdresser he was and that he was a drag queen. He was always taking people under his wing and trying to mentor them and teach them. I tried to bring in those little bits that showed people he was a human being, and that he had people who missed him and were, you know, negatively impacted by his passing.

Key art for HBO’s two-part documentary Murder in Glitterball City, premiering Feb. 19, which revisits the Old Louisville murder case through a queer cultural lens.

You’re also documenting LGBTQ+ and drag culture in Old Louisville for the docuseries— a world that hasn’t been extensively written about in this context.

Yeah, it’s kind of a fine line. There’s this sensationalism, the tawdry, titillating miscellanea. But then, you want to do a fair job representing a culture, and I think it worked for me.

I was kind of intending to do that because it’s a gay neighborhood, a gay couple, a gay victim, and a gay author, and then, when HBO comes in, it’s a production company known for its LGBTQ+ documentaries and movies. You’re representing a culture indirectly, want to do right by them, but don’t want to shy away from sensitive issues or be seen as covering up for anything.