PART ONE At the crossroads of class struggle and religious bigotry: field notes on Louisville’s coffee scene

He/Him

[email protected]

Editor’s Note: Adrian Silbernagel is a former employee of Heine Brother’s Coffee and is currently one of the co-op members of Old Louisville Coffee Shop. We understand that a bias exists, and we also know that this story is incredibly important and we’ve matched commentary with factual information. You can always send a letter to the editor at [email protected] and please copy our board chair at [email protected]

The present moment

Years ago, public media outlet WFPL published an article by a journalist named Gabe Bullard, called “How Christianity Shapes Louisville’s Coffee Culture.” The article made waves, so much so that local baristas and coffee shop patrons are still talking about it today.

Over the next couple of months, Queer Kentucky writer Adrian Silbernagel, will be revisiting the themes in Bullard’s article, and a few others, through a queer, critical lens. These themes include, but are not limited to: how Southern Baptist Christianity has shaped Louisville coffee culture; the dark history of Southern Baptist Christianity, its local history in particular; the characteristics and dangers of “hipster Christian culture” which is a commonly discussed trait of Louisville’s Sojourn Church; and local coffee chains’ anti-union sentiments. This work of investigative journalism will be published in timely installments.

A lot has happened in Louisville since 2014, the year Bullard’s article was published.

“Business as usual” was necessarily disrupted in the wake of Breonna Taylor’s murder, and for months after. Schools, churches, leaders, and businesses—including coffee shops—were put on blast for their involvement or complicence in racism. Louisville businesses came under greater scrutiny, as did the city of Louisville, resulting in a heightened self-awareness among our city’s powerholders. Louisville activists continue to apply pressure, preventing a return to the status quo.

Greater trans visibility has triggered waves of anti-trans legislation, putting trans rights at the forefront of LGBTQ+ advocacy and activism, in the workplace and beyond. More and more workplaces are investing in trans inclusivity workshops and consultants, an investment that can make a world of difference for queer and trans folks on both sides of the counter. And the more businesses that make that investment, the more likely queer people are to expect the same of the companies they work for and/or frequent.

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade on June 24, causing abortion bans to go into effect in many states, more and more workers of every political orientation have been awakening to the realization of just how undemocratic America actually is, and how many of our hard-won civil rights could be revoked overnight, at the whim of a few all-powerful individuals.

Meanwhile, COVID continues to mutate, and capitalism continues to show its true colors (and ours). For example, when the pandemic first hit the U.S, many employers responded to their plummeting sales by laying off the workers they could no longer afford. Other employers, to avoid a spike in unemployment tax rates, drastically cut their workers’ hours, effectively driving many of them to quit (and thus to forfeit their unemployment benefits). According to the latter employers, their under-scheduled workers “could always pick up shifts at other locations” if they were that hard up for hours. (Of course, the workers would not be compensated for the added labor of hustling for shifts, the increased risk of exposure to the virus, the sudden lack of guaranteed income, or the stress of adjusting to a whole new work environment.)

When more and more workers fell ill, suffered burnout, and/or became fed up with employers who were intentionally starving them of hours, the tables started turning. Employers found themselves in a “worker shortage” and workers started to become aware of their collective power. Those who could not join in the Great Resignation became a part of the great awakening: all of us—workers and employers both—were reminded just how essential workers are, and how, without us, the company will not do any business.

Louisville coffee culture continues to change rapidly as businesses adjust to and embrace the new normal (closing earlier, eliminating non-drivethru stores, permanently retiring condiment counters) and as workers all over the city become more radicalized, unionizing their workplaces and taking control of the narrative on social media and in the news stories that feature them.

As America’s majority grows poorer and inflation is not matched by wage increases, the class war between workers and employers intensifies. As of November 21st, the average rent for a 1-bedroom apartment in Louisville, KY is $1,119: a 17% increase from 2021, despite the fact that there was a slight decrease in median household income in Kentucky from the previous year in 2021. Bear in mind, these numbers are just averages. The situation is even more dire for queers, particularly for trans people and/or POC. (See the graph below.)

Some ignore the coming recession, while others continue to fight for a revolution. But wherever we are headed, this much is certain: we are living in a historical moment: as workers, as coffee drinkers, and as queers. But to gain some perspective on the present, let’s take a quick trip back to a simpler time: a time when the hottest piece of gossip in Louisville was a scandal involving a local Christian coffee shop, a local indie publication, and a bunch of angry queers.

Where are your bibles?

In 2014, WFPL published an article titled “How Christianity Shapes Louisville’s Coffee Culture.” The article is written by Gabe Bullard, a journalist, audio producer, and public media strategist who writes primarily about culture and history, with topics ranging from the global growth of atheism and secularism to the Cancel The Rent movement to the “weird history of hillbilly TV.”

Based on his portfolio, Bullard seems to be the type of journalist NPR might hire. (Indeed, WFPL self-identifies as the NPR of Louisville). But beneath Bullard’s seemingly liberal subject matter lies a socially conservative subtext posturing as nostalgia: a longing for the “good old days” when families went to church on Sundays, and when “the most consequential difference you could find on TV” was cheeky satire about the present day versus sincere portrayals of an idealized past.

The article begins:

A woman walks into Sunergos Coffee on Preston Street in Louisville. She orders a drink and begins looking around, through the mixture of cafe settings and living room couches. She’s looking for something. She doesn’t find it. She returns to the counter, upset.

“Where are your bibles?” she asks.

“I…I have one,” says the woman working at the shop.

“Where are your bibles here?” asks the customer.

“Well there aren’t any,” says the barista.

The customer replies, “I thought you were a Christian coffee shop.”

This story comes from Matthew Huested, the co-founder of Sunergos. He tells the story when someone says a church, not Huested, owns Sunergos, or when they say his employees are all Baptists bent on converting customers. It’s a persistent rumor, largely unique to this city.

Introductory paragraphs typically function to illuminate or lay out a path for the reader, so as to prevent them from getting lost. This introduction does the opposite: it raises more questions than it answers. If Huested is bothered by the “persistent rumors” Louisvillians spread about his business, why doesn’t he clear them up? To me, the story comes off as coy: Huested likes the rumors, or the attention they give his business, but he’s not about to say this.

However you interpret it, the story (parable?) and its punchline (moral?) obfuscates rather than illuminates. The article continues in this same fashion: Ballard brings to light “rumors” about various coffee shops and their owners’ religious and political commitments, then he challenges or even rejects those rumors, and then he goes on to present evidence in their defense. But to what end?

I don’t think Huested is trying to sound like the grasshopper in an Aesop’s fable for its own sake. I do think he is being intentionally elusive to avoid having to say what he really means, or believes, or wants for his business. And I think the same could be said about Ballard and his journalism.

But enough with my textual analysis. It’s time for some drama.

The LEO controversy

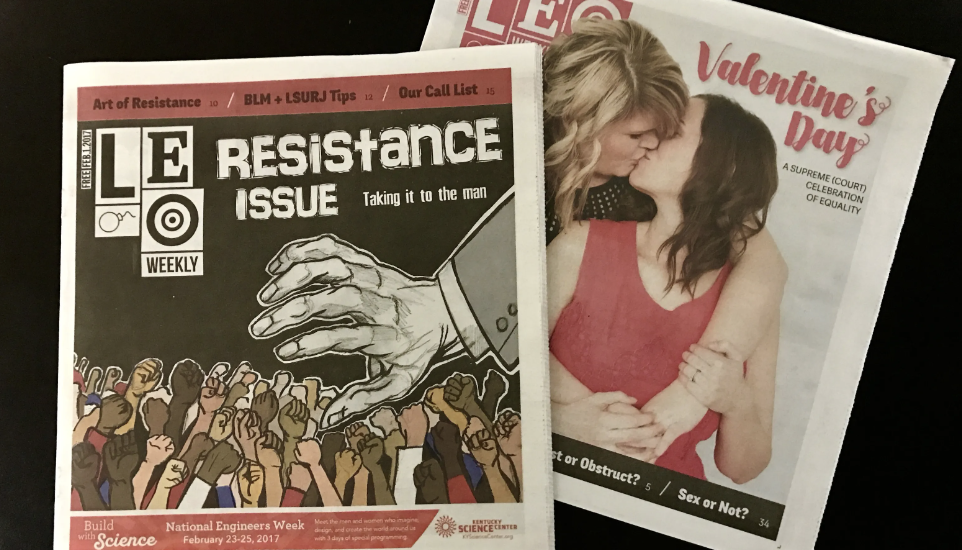

On February 10, 2017, the tea was hot in Louisville. Word among the gays was that a popular Louisville coffee chain (Sunergos) had stopped carrying a progressive magazine (the LEO) because the Christian company was offended by the most recent Valentine’s Day issue by Allie Fireel which featured four recently-married gay couples, and had a picture of two women kissing on the cover. Sunergos went on the record saying that, actually, they decided to stop carrying the magazine days before the issue in question was released, and their decision was based on the publication’s adult advertisements (e.g. strip club ads and razor adds with “nakedly” pictures of women shaving) which they felt contradicted their values as a “family friendly” establishment. They even provided dates to corroborate their story: they had canceled their subscription on the first of the month, and the Valentine’s issue came out on the eighth.

For many in the community, Sunergos’s response left much to be desired, especially in the current climate. Between gay marriage being declared legal, the subsequent backlash from the Right and folks Kim Davis, the horror of the Pulse shooting, the horror of the 2016 election, all the bigotry that came out of the woodwork when Trump took office—our community had just been through lot. Anyone paying attention knew where our anger and mistrust was coming from. But instead of acknowledging and speaking to those feelings, Sunergos became defensive, arguing over technicalities like they had been issued a parking ticket when the street sign was worded ambiguously.

Around this time, I was getting ready to move to Louisville. My partner had been accepted to a grad program at UofL, and I had just been through a tumultuous couple of years transitioning. I was ready for a new beginning, I just needed to find a job. In Lexington I worked at a coffee shop called Coffea. Coffea (which is now closed) served Sunergos coffee, a partnership that included off-site trainings for Coffea baristas. A couple times a year, we would pile into a car and make the drive up to Louisville for a day of cupping and milk steaming.

Given my background in coffee and my existing knowledge of their brand, applying to Sunergos seemed to be the logical next step. And then the LEO controversy happened, sparking outrage in Louisville’s queer community and spreading like wildfire to Lexington. A trans man still early in my transition, I didn’t want to risk getting stuck working for another transphobic employer so I decided to do some more research. As I scoured the web, I stumbled upon Bullard’s article, which solidified my decision to not apply to Sunergos, and changed my whole life course. I went to work at Heine Brothers,’ and stayed there for the next five years, spending the last four managing their Douglass Loop location: the location that was shut down earlier this year (another big controversy that made the news). By this time, me and a few other former-Heines were getting ready to open our own shop: Old Louisville Coffee Co-op. Incidentally, Douglass Loop closed its doors the day after our grand opening.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!