Twink, bear, Otter Creek, OH MY! Let’s talk about the first Kentucky Pride

*Had to sign a Copy Service Agreement and Permission to Publish forms with U of L Special Archives to use the first pride flyer and Lavender Letter images*

he/him/his

From my younger days, to when we moved to Meade County when I was in sixth grade and now into adulthood, Otter Creek Park has been in my life. It is where I went to Boy Scout events as a child, where my dad took me to play disc golf with him, and where I still take my autistic brother on our endless search for geodes. Though I have been there numerous times and seen quite a bit of wildlife, if I had been around in 1982, I might have seen a twink, a bear, or an otter. This is because the first Pride in Kentucky was held that year at Otter Creek Park.

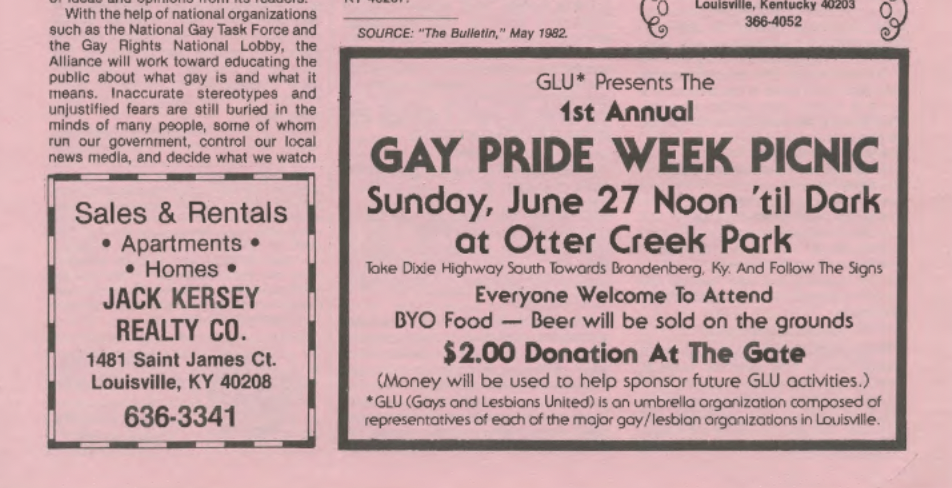

It was held June 27, 1982 from noon till dark as the flyer states. It was sponsored by GLU (Gays and Lesbians United) and required a two dollar donation to attend. According to Bassett (2017) activist Ken Herndon stated the picnic drew about 100 people. Ken recalls thinking if it’s called Pride, why was it 45 miles out of town (Bassett, 2017). This was for cautious reasons as those that attended didn’t want to be outed to their families or employers at the time (Bassett, 2017).

This information and flyer below were provided by the University of Louisville’s Williams-Nichols Collection, Archives and Special Collections. The University of Louisville has this collection because of David Williams (Lally, 2022). David kept every bit of information, flyers, buttons, newsletters related to the LGBT rights movement in Kentucky, since it started (Lally, 2022). According to Lally (2022) it took a large truck and four hours to unload the first of his collection to UofL. It was this collection that helped researchers, through a special project the National Park Service and other local organizations started, to create the Kentucky LGBTQ Heritage Project (Snyder, 2017). The name of the archives comes from David’s last name and his late partner Norman’s last name, who passed away during the AIDS epidemic (Lally, 2022). David is quoted as saying “I was trying to think practical and not think about the sadness that might ensue, so I thought to memorialize Norman and named the archive then the Williams-Nichols institute” (Lally, 2022). He also thinks it might be the only archive library in the nation named after two gay lovers (Lally, 2022).

(Courtesy of Williams-Nichols Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Louisville)

I think about all the history that would have been lost without his personal collection and the National Parks System starting this project. Not only that but all the history we know nothing about because of the stigma surrounding the LGBT community throughout the years. I had no clue that such an important event happened less than ten minutes from where I grew up and in a rural part of Kentucky. From the experiences I’ve had in growing up here, it blows my mind that it occurred so close to me.

(Courtesy of Williams-Nichols Collection, Archives & Special Collections, University of Louisville)

I was shocked upon finding this out for several reasons. I remember in high school the controversy of a Hispanic man being beaten by the Ku Klux Klan at the Meade County Fair. Jordan Gruver was attacked at the fair by members of the Imperial Klan’s of America, which is allegedly the second largest Ku Klux Klan group in America (Avila & Tribolet, 2008). He was kicked with steel-toed boots and left with a broken jaw (Avila & Tribolet, 2008). Two years after the attack happened, Gruver was awarded $2.5 million from two Klansmen who were responsible for the attack (Avila & Tribolet, 2008).

I recall time spent in my high school journalism class. We were told explicitly that we were not allowed to write about LGBT issues for the school paper. Our journalism teacher wouldn’t fight them on this restriction. Then there is the bullying I would experience during my time from sixth grade till graduation. My mentality was just to blend into the background and not cause a commotion so I could get through school. There also existed no gay/straight alliance during my time there. Then you step into the dispute between heritage vs hate, as down the road from Otter Creek in downtown Brandenburg, sits the massive confederate statue, which used to be on UofL’s campus. Some say this monument is about remembering history, but I say it honors the wrong side of history and I view it as a shining beacon for those with racist beliefs, like those in the KKK.

This isn’t to say that there exists no good or welcoming people here, and times have changed since I graduated high school. They do have the confederate monument, but they also, albeit considerably smaller than the confederate one, monuments to Native Americans and African-American slaves crossing the river to Indiana for freedom. The old Brandenburg ferry was a major artery of the Underground Railroad into Indiana to help them reach freedom. Since my departure from high school, they have become more accepting. During my brothers time in high school he was part of the new gay/straight alliance. Also, as part of my volunteer work for our local domestic violence shelter, Meade County let us hang a domestic violence awareness quilt, with survivors and politicians hands outlined, permanently in the local courthouse.

If they can memorialize the confederate soldiers, then we should be able to honor the first pride happening at Otter Creek. The state should put a historical marker at Otter Creek Park to signify the first Pride. This would help us to remember our LGBT past but also as a way to show that the LGBT community is also in rural areas. There is estimated to be almost 3 to 4 million LGBT people living in rural America (Fadel, 2019). To put it in perspective that is 5% of the rural population is LGBT and 20% of the LGBT population is living in rural areas (Fadel, 2019).

I know this to be true because I am part of that population who is living in a rural area. I grew up in Meade County and currently live in the next county over. Growing up here has come with struggles and seeing a historical marker, showing the first pride happened in a rural area, could have been life changing. We need more representation in rural areas. Growing up I always thought I would get out of here and move back to Louisville or another urban area.

I am beyond glad that I never followed through. Staying rural lead to many great things in my life. I found my husband, my friends, got my college education here and built our own home on what used to be my father-in-laws hay field. (Side-Note: some of my nearest neighbors are cows)

We may not be as flashy or open as those in urban areas, which could be from being on edge slightly more, because of the attitudes and pre-conceived notions some people have about the LGBT community. Nonetheless, we are here and we are rurally queer. I feel that we shouldn’t have to leave where we grew up, unless you want to or need to. I’ve felt that the rural life is more my speed and I want to be here. I want to be here because if we all abandon here, that only leaves those with closed off ignorant views living here. I want to fight for my community to become more accepting of the LGBT community and that starts with me being me, in a rural area.

Having a historical marker and knowing that the first pride in Kentucky happened so close and in a rural area, could help make this happen. You don’t have to be or live in a certain place to be LGBT. I know there is amazing, good hearted people here and hopefully as we live more openly, discover our history, and build new paths into the future, we will create the world that might only be in our imaginations right now.

Sources:

Avila, J., &, Tribolet, B. (2008, November 17). Klan Leader, Former Member Ordered to Pay $2.5M in Attack. ABC News. Retrieved September 12, 2022, from https://abcnews.go.com/TheLaw/story?id=6270127&page=1

Bassett, T. (2017, February 15). The roots of pride: The deep roots of kentuckiana pride. LEO Weekly. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.leoweekly.com/2017/02/roots-pride-deep-roots-kentuckiana-pride/

Fadel, L. (2019, April 4). New study: LGBT people a ‘fundamental part of the fabric of rural communities’. NPR. Retrieved September 12, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/2019/04/04/709601295/lgbt-people-are-a-fundamental-part-of-the-fabric-of-rural-communities

Lally, T. (2022, June 22). Meet the man behind one of the largest LGBTQ+ archives in the country. whas11.com. Retrieved September 6, 2022, from https://www.whas11.com/article/news/community/moments-that-matter/louisville-lgbt-history-ekstrom-library-collection-archive-david-williams-kentucky/417-b72d609a-8fa2-4410-b309-0ed5853ba173

Synder, L. (2017, March 20). A look back at the pioneers of Kentucky’s LGBTQ movement. LEO Weekly. Retrieved September 6, 2022, from https://www.leoweekly.com/2017/03/a-proud-history/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!