The Downstairs Club: A History of the Segregated Queer Haven in Kenton County

Along the winding stretch of Madison Pike—known locally as the 3-L Highway, just outside of Covington—where gas stations, roadside diners, and farm stands dotted the landscape, one unassuming building held a secret. At first glance, 456 Madison Pike looked like little more than a modest bar tucked into the hillside, its roof barely visible from the parking lot. But for those in the know, this was The Downstairs Club—one of the most infamous and cherished queer gathering places in the region from the late 1950s through the 1970s.

Hidden in the rolling hills of Kenton County, its remote location offered a paradoxical mix of isolation and protection. Beneath the cover of darkness, LGBTQ patrons from Kentucky and Ohio found more than a bar; they found a sanctuary. Here, in this smoky underground haven, affection could unfold freely, forging deeper connections and strengthening a community that so often had to exist in secrecy. Unlike the fleeting, often dangerous encounters in surveilled parks or shadowed street corners, The Downstairs Club offered something rare—embraces without fear, conversation without pretense, and the simple yet radical act of being seen.

Longtime patron Scott Parker, who threw a reunion for former patrons The Downstairs Club at Below Zero in 2016, recalled that the bar welcomed icons like Little Richard and Jimi Hendrix, describing it as “known from coast to coast for its uniqueness and the very special place that it was.” He was interviewed for a story about the reunion put out by the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce Newsletter that year, “This was in the 1960s and early ’70s when, in more liberal parts of the country like Los Angeles, dancing was not allowed in gay bars and nightclubs,” he said. “Nowhere in the city of Los Angeles was dancing allowed. Now you can understand how unique The Downstairs Club was during this period. It was truly ‘one of a kind’ and ahead of the times.”

The club had first opened under the name The Jochebo, a moniker derived from the first three letters of the names of its founders—the Speakes family. John T. “Jack” Speakes, a former U.S. Army corporal, and his wife, Helen, had already operated another queer-friendly bar, The Riviera (not to be confused with a different bar of the same name that opened in the 1970s). Their son, Bobby Combs, became a fixture in the local queer scene, earning the nickname, “Darling of The Downstairs Club,” for his quick wit and charm. He later ran That Darn Pussy Cat, a Newport go-go bar that law enforcement targeted for allegedly existing “specifically and entirely to encourage, incite, create, permit, and entice persons who practice homosexuality.”

For years, it was an open secret that the Speakes family had ties to what remained of organized crime in the region—connections that, for a time, seemed to shield them from police interference. But that protection unraveled in 1962 as both Cincinnati and Covington sought to suppress the city’s growing and undeniable queer subculture.

In June, a Kenton County judge denied Jack and Helen Speakes an entertainment permit for The Jochebo Club, citing illegal operation and fostering obscenity. Testimony from law enforcement officers painted a damning picture, and the judge condemned the club for defying state laws. Local newspapers echoed the court’s outrage, labeling the venue a den of vice frequented by “sex deviates” and “so-called queers.”

Yet despite these legal battles, The Downstairs Club remained resilient. In May 1965, The Cincinnati Enquirer alluded to its endurance, questioning delays in legal proceedings against regional gambling dens and remarking, “Understand that there is a basement bar in Kenton County that is getting its fair share of homosexuals as customers.” By 1968, Kentucky’s Alcoholic Beverage Control Board vowed to crack down on “taverns that cater to homosexuals” in Northern Kentucky. That same month, The Enquirer issued another thinly veiled warning:

“While Covington Police are cracking down on gambling and vice in their city, they might also take a look at a basement night spot that is crowded nightly with homosexuals. Narcotics agents might also take a look at the place.”

Yet, for reasons unknown, The Downstairs Club remained largely untouched after 1962. Whether due to lingering political connections, selective enforcement, or sheer luck, the club continued to operate, providing a rare and vital refuge for its patrons.

For all its reputation as a liberated space, the club, like most LGBTQ venues of the era, remained deeply segregated. Even after the end of legal segregation, de facto barriers persisted—Black gay men and women were often required to have white co-signers or present multiple forms of ID to gain entry.

Cincinnati activist Mary Ann Lederer, whose visit to The Downstairs Club helped inspire her activism and the founding of the city’s first gay rights organization in 1967, was dismayed to discover the club’s strict enforcement of racial boundaries. She recalled in an interview with local lesbian activist Phebe Beiser in a publication entitled Dinah the 1980s:

“I felt I should boycott the place, but this was the only gay bar I really enjoyed. I had waited many years to find it and didn’t want to give it up,” she said. “I decided to integrate it from the inside out. I went back and talked to the owner’s son, who was gay. He seemed to wish it were integrated but thought this was impossible. After all, Kentucky in the early ’60s was really South.”

It was published in Dinah, a local lesbian publication that ran throughout the 1970s and 1980s and & To the Roots, a periodical that ran briefly for two or three issues in 1988. “To The Roots.” Dinah: “Interview with an Activist.” Summer 1988. Issue 1 Volume 1. Interview by Phebe Beiser of Ohio Lesbian Archives. publication of the Lesbian Activist Bureau, Inc. Page 16.

For all its defiance of mainstream social norms, The Downstairs Club upheld the same racial exclusions that pervaded much of American society. This reality complicates any nostalgic view of the club, forcing us to reckon with the exclusion embedded in queer spaces of the past. For many, this underground refuge remained just that—a refuge, but only for those who met its unspoken criteria.

By the 1970s, the club finally desegregated, following other businesses in slowly adapting to social change. Yet the legacy of segregation in queer spaces lingers, with Black and white LGBTQ social circles often remaining divided to this day.

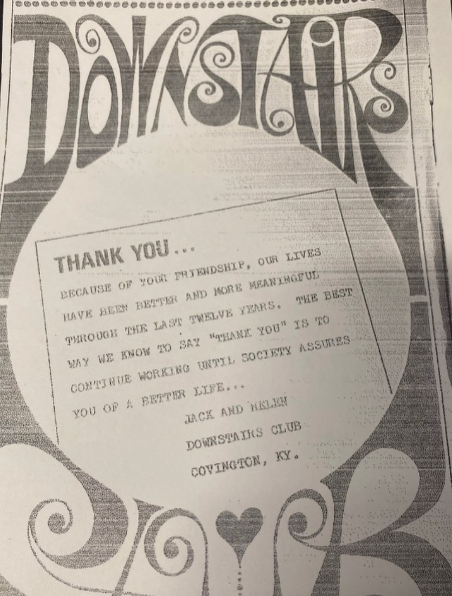

The Downstairs Club’s eventual closure remains somewhat shrouded in mystery, as is often the case with clandestine spaces that exist on the margins of legality. Some accounts suggest that as LGBTQ rights gained more visibility and larger cities offered more welcoming environments, the need for a hidden, rural sanctuary diminished. Others speculate that law enforcement pressure, or perhaps a shift in ownership, led to its end. Whatever the reason, by the late 1970s, the club had faded into history, leaving behind only memories and scattered mentions in legal records and personal accounts.

The story of The Downstairs Club is one of resilience, secrecy, and the relentless need for spaces where queer people—against all odds—could find community, even in the most unexpected corners of America. It was a place of laughter, of love, of dancing in defiance of a world that demanded silence. It was a place where, for a few precious hours, people could shed the masks they wore in their daily lives and simply exist. But it was also a place where the wounds of racism and exclusion mirrored the broader struggles within the LGBTQ community itself.

Remembering The Downstairs Club means remembering both its triumphs and its failings. It means honoring those who built, defended, and ultimately lost this sanctuary. And it means continuing the fight for spaces where everyone, regardless of race, gender, or sexuality, can find a home.